TL;DR: What counts as a language? The definition of a “language” can be ambiguous and subjective. There are some distinct “languages” that are very similar to each other, and some “dialects” of a single language that are very different from each other.

Previously, I wrote an article here called “Best foreign languages to learn?”. As I was doing research for it, I stumbled on this problem. It’s sometimes difficult to classify what exactly constitutes a language. Here I discuss a few examples of when that distinction became hazy.

| Contents: |

| Chinese |

| Hindustani |

| Serbo-Croatian |

| Arabic |

Chinese

The Chinese writing system is pretty unique in the world today. Like ancient Egyptian hieroglyphics, Chinese characters are based on pictographs. They essentially use pictures to convey meaning. For example, the character for “person” is 人. The character for “tree” is 木. And the character for “rest” or “a break” combines these two characters to make 休 (like a person leaning to rest against a tree).

So unlike in English and other languages, Chinese characters don’t say anything about the pronunciation of a word or phrase (though certain sets of characters do follow some broad pronunciation patterns). Instead, each character contains one or more parts implying the overall meaning of the character.

China is a huge country with a long history. Because of that, and because its characters don’t really have specific pronunciations attached to them, large differences have developed in the Chinese spoken in different parts of the nation. Often Chinese speakers from one part of China can’t understand what another dialect’s speakers are saying. In other words, the different dialects aren’t ‘mutually intelligible’. In fact, these dialects can be much less mutually intelligible than, for example, spoken Spanish and Portuguese.

Today, Mandarin Chinese is the official language of China as a country. Almost all Chinese people speak Mandarin, at least at a basic level. But there are many other varieties of Chinese as well. These are written essentially the same as Mandarin, but not mutually intelligible in speech. Around the 1960’s, a system of categories became popular for classifying these dialects into seven broad groups. Each group is often considered its own language—or even group of languages—by modern linguists. These are the seven traditional groups, along with more common variety names:

- Mandarin

- Yue (Cantonese)

- Wu (Shanghainese)

- Min (Taiwanese)

- Gan (Jiangxinese)

- Hakka

- Xiang (Hunanese)

These are listed approximately in order of how many people speak them in China. Except for Mandarin, each of these dialects is spoken as a first language by around 5% of the population. More than 60% speak Mandarin as a first language. During the second half of the 1900’s, the Chinese government has tried to unite its people around the official Mandarin variety of Chinese. It is by far the most common dialect, after decades of active government support. Mandarin is still basically a lingua franca across all of mainland China and Taiwan.

There has also been increasing interest in the other dialects, though. These different dialects each have their own unique history and culture (see here, for instance, for more details). In recent years, some experts have suggested classification systems with more than just these seven categories. But this seven-dialect system is still commonly used for now. For the “Best languages” article, I used this grouping and considered Chinese as seven separate languages. I still acknowledge, though, that there are arguments to be made for different groupings and categorization.

Hindi-Urdu-Hindustani

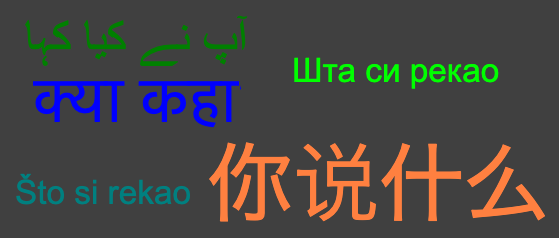

Moving from East Asia to South Asia, we find India and Pakistan. They respectively have official languages of Hindi and Urdu. With Chinese, we saw multiple non-mutually intelligible dialects using the same writing system. With Hindi and Urdu, we see the opposite. These languages use two completely different writing systems for fundamentally mutually intelligible dialects.

Hindi and Urdu are basically two different versions of the same root language. The two languages are sometimes classified as a single language. This single language is sometimes referred to as Hindustani. The writing systems are where the most obvious differences start. Hindi uses a left-to-right writing system, with a type of alphabet known as an abugida. In an abugida, you mostly only write consonants. The vowel after each consonant gets written as a little mark somewhere next to the consonant. Urdu, on the other hand, uses the same writing system as Persian (Farsi). This is a cursive right-to-left script based on Arabic, an alphabet known as an abjad. In an abjad, vowels traditionally aren’t notated at all, basically just inferred from context.

In this difference, we start to see the cultural differences behind the two separate languages. The Devanagari abugida writing system used in Hindi comes from the ancient Brahmi script. The Brahmi script was the first writing system we know of that was used for writing the Sanskrit language. Sanskrit is the sacred language of Hinduism, and also important to other Indian religions such as Jainism and Buddhism.

Of course, Urdu uses essentially the same writing system as Arabic, the sacred language of Islam and the Muslims. Urdu also more often uses loan words from Persian, where Hindi typically tries to use vocabulary from its Sanskrit roots. So these languages maintain separate writing systems, and they get get their vocabulary from different places. Different patterns develop in the two languages, and they gradually shift further apart.

In his time, Mahatma Gandhi advocated for the two dialects to be regarded as one Hindustani language. That sentiment didn’t really win out in the end, as we see with Pakistan’s split off from India in the late 1940’s and the accompanying conflict. Hindi and Urdu are now each a widely spoken language and important lingua franca in their respective countries. I still see some sources categorize them as a single Hindustani language, but there’s definitely also good reason to consider them as separate.

Serbo-Croatian/Shtokavian/BCMS

Remember the multiple writing systems for Hindustani? The same thing happened for the southwest Slavic languages, at a larger scale. The Serbian language uses the Cyrillic alphabet, the same one that Russian uses. Croatian, Bosnian, and Montenegrin, on the other hand, all use the Roman alphabet, basically the same one that English uses. And all four of these languages are quite mutually intelligible with each other.

There’s a former country called Yugoslavia that existed up until a few decades ago. Until the late 1990’s, Serbia, Bosnia, Croatia, and Montenegro were all part of Yugoslavia. That larger country broke up, amid violent wars. In its place, there are now six or seven independent countries. Four of them are Serbia, Bosnia, Croatia, and Montenegro.

Each of these countries has its own language: Serbian, Croatian, Bosnian, Montenegrin. Linguists often consider these all the same language. The vocabulary and grammar are almost identical between them. Serbian uses the Russian (Cyrillic) alphabet, perhaps to help strengthen ties with Russia and eastern Europe in general. The other three using Latin script, the same as English, may help position them as more Western-facing. Each country defines its own slightly different version of the language, part of an effort to establish independent identities.

All these languages are Slavic, the same language category as Russian, Polish, and some other eastern European languages. The similarities and differences between each of the four may partially reflect the complex relations between each country, and with outside countries.

Arabic

Arabic is spoken widely across Africa and Asia. It’s the official language of 26 different countries. Usually, at an official level, this refers to “Modern Standard Arabic” (MSA). MSA is the kind of Arabic these countries use for textbooks, newspapers, and so on. The actual Arabic spoken in these countries, however, can be very different from MSA. Some varieties are so different that they’re hardly mutually intelligible to each other.

Like with Chinese, one way to handle this variation is to break the varieties down into groups. For Arabic, one common system breaks the varieties down into five groups (source). Those groups are:

- Maghrebi (North Africa)

- Egyptic

- Mesopotamian (Iraq/Syria area)

- Levantine (Lebanon/Israel area)

- Peninsular Arabic (Saudi Arabia area)

Some linguists may consider each of these as its own language or even group of languages. For religious and cultural reasons, though, the official language in all these countries is just “Arabic”.